Former political prisoner shares his experience in Russian prison in Donetsk

Looking back at his time in captivity, Stanislav Aseyev can confidently identify only one time when he gave up utterly and completely.

“Neither being held prisoner, nor the torture have had such a devastating effect on me,” Aseyev says in his book The Torture Camp on Paradise Street. “These people, who were so insistent on humiliating me and worked so hard to atomize my personality into little pieces, had no clue that they could have gotten me to do anything right there and then.”

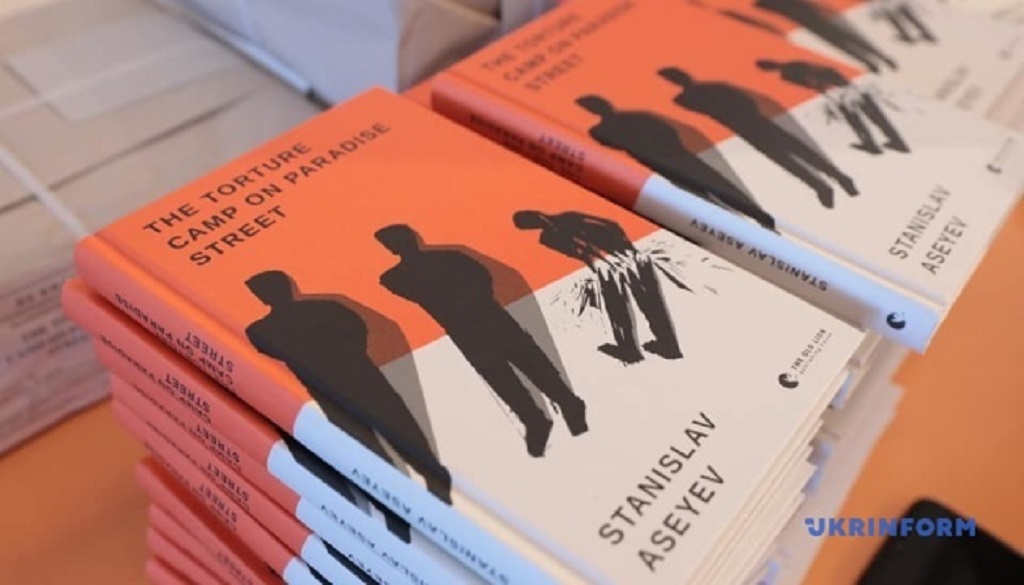

Aseyev presented an English-language edition of his book on October 13. The presentation was a part of the campaign to raise international awareness of human rights violations and illegal activities of Russia on the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine. The ultimate goal of the presentation was bringing the closure of the illegal prison “Izolyatsia” and other similar illegal facilities.

A native of Donetsk, Stanislav Aseyev worked for Radio Free Europe for two years following Russia’s invasion of Eastern Ukraine. He authored unbiased reports about the on-the-ground reality in occupied Donbas for media outlets in Ukraine under the penname Stanislav Vasin. Until his capture, his reporting was an important source of information about Russian-occupied Donetsk.

In June 2017, Aseyev disappeared, having been captured and unlawfully imprisoned by the Russian occupation forces in Donetsk. Sentenced to fifteen years on trumped up terrorism charges, Aseyev spent thirty-two months in unsanctioned Donetsk prisons, where he was brutally and routinely tortured. Aseyev spent almost 1,000 days imprisoned; 28 of them he was kept in an unofficial torture prison for “especially dangerous prisoners”.

“I had no inkling yet of the scale of Donestk’s underground torture operation or the fact that in that very building, 99 men out of each hundred were tortured,” said Aseyev.

He was still being held in the solitary cell in the basement, before being transferred to “Izolyatsia”, when one day he was brought out and driven beyond the city limits for the purposes of so-called ‘investigative actions’.

“As fate would have it, we drove past my old neighborhood; meanwhile, my hood had been pulled off since leaving the city,” he writes.

“I looked out the van window and pictured my mother, in a room by herself, by the phone. She had just made a call to another morgue. Or perhaps she was crying, defeated by the not-knowing: she couldn’t even find out if her son was alive.”

“I saw all those things and knew that I could cover the distance that separated me from my mother in three or four minutes. Then I could hug her. But I am being taken back to the basement: the vision flits by and is gone, like a dream.”

“All I wanted was to be shot — such was the depth of my despair.”

The presentation was organised by the Embassy of Ukraine in Canada, Ukrainian Canadian Congress and Embassy of Canada in Ukraine.

“It’s about horrors of what men will do to men, what people will do to each other,” Canada’s Ambassador to Ukraine Larisa Galadza said during the presentation. “And it is, unfortunately, yet another way of describing what the war, what Russian aggression looks like, on the territory of Ukraine.”

“People might get tired of talking about it,” Galadza said. “People might get lost in numbers, in statistics, people might lose the track of the ceasefire violations or what’s happening in the Minsk process.”

“But when you read Stanislav book, you get yet another window into what Russian aggression looks like, what it looks like on the human spirit, and the length that they will go to crush the human spirit,” she said.

“It is very important for understanding of the scale of the evil, and also for the legal definition of what is happening there,” said Ukraine’s Ambassador to Canada Andriy Shevchenko. “Stanislav helps us to understand that what we deal with is a crime, it’s a war crime, it’s a crime against humanity. And the hope is that this will help to bring justice to those responsible for this.”

‘“Izolyatsia’ is not about war. It’s about human being. And when we, together with the UCC, brought Oleh Sentsov to Canada, he did not want to talk much about his time in Russian prisons. He told me ‘there is nothing fancy, nothing good or interesting about it”. And I’m not sure we want even to picture those terrible things that Stanislav had to go through and see around him. But we know that his words, his painful truth, will help people to get strength,” Shevchenko said.

The Torture Camp on Paradise Street, a memoir of his imprisonment and an exposé of the “Donetsk Peoples Rupublic’s” underground prison system, was published in Ukrainian in 2020. The English translation of the book was made possible thanks to the Embassy of Canada to Ukraine. In Isolation: Dispatches from Occupied Donbas, a collection of Aseyev’s reportages from war-torn Donetsk, will be available in English in late summer from The Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. Aseyev is also the author of the novel The Melchior Elephant, or the Man Who Thought, a collection of poetry, and a play. He is the recipient of the 2020 Free Media Award, the 2020 National Freedom of Expression Award, and the 2021 Taras Shevchenko National Prize for his journalistic writings.

This article is written under the Local Journalism Initiative agreement

Kateryna Bandura for New Pathway – Ukrainian News

Follow me on social media!You May Also Like

UCC calls on government to provide defensive weapons to Ukraine

January 26, 2022

UofM panel reflects on legacy of Holodomor

November 30, 2021